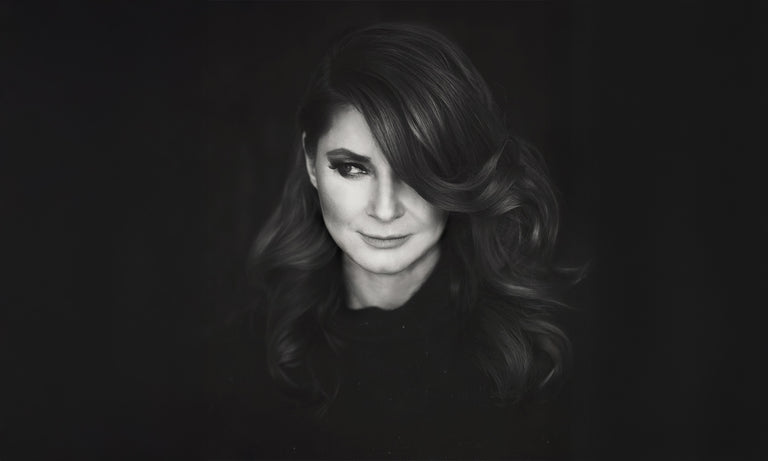

Marlies Says

The feminist fairytale behind the star of the norwegian sweater

Discover the inspiring origin of the iconic Norwegian 'selburose' snowflake pattern. From a young girl’s handmade mittens to a national symbol of independence and empowerment, this fairytale knits together history,...

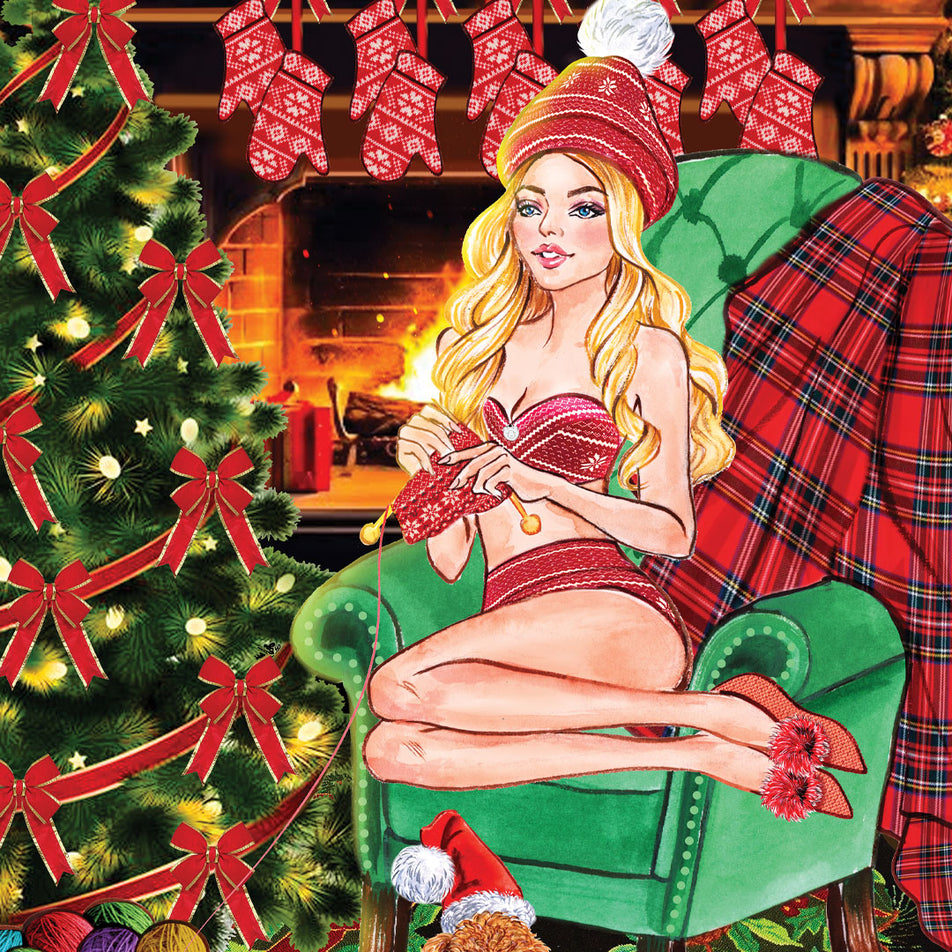

I have always loved a cozy, handknitted sweater. And nothing quite says: 'bring on the winter!' like a traditional Norwegian 'snowflake' pattern: the perfect combination of comfy, crafty and classy. But did you know that woven into this ancient design is a fairytale of hope and female empowerment? Pour me some hot cocoa and I'll tell you the story...

I have always loved a cozy, handknitted sweater. And nothing quite says: 'bring on the winter!' like a traditional Norwegian 'snowflake' pattern: the perfect combination of comfy, crafty and classy. But did you know that woven into this ancient design is a fairytale of hope and female empowerment? Pour me some hot cocoa and I'll tell you the story...

Once upon a time, a girl named Marit Gulsethbrua Emstad knitted three pairs of black-and-white mittens with a gorgeous, eight-pointed star pattern. When she showed them off at her church in Selbu, a small town in the middle of Norway, the locals went crazy. Everybody wanted a pair. This took place in 1857, and little did Marit know that within a few decades, the 'selburose' pattern would be one of Norway's most beloved symbols, while the production of her mittens would provide several generations of knit-handy Norwegian women with financial independence and freedom.

Where did Marit get inspiration for her pattern? And what does that beautiful snowflake stand for exactly? Some see an eight-bladed rose design (åttebladrose); hence the name 'selburose'. Others claim it's Polaris, the North Star that can be found almost directly at the Earth’s North celestial pole (it is a more consistent navigational tool than a magnetic compass). The Sumerians - one of the oldest known civilizations - already used an eight-pointed star in their mother-of-pearl mosaics, calling it the Star of Ishtar, after their goddess of love, lust and war. Throughout the ages, it would pop up on Medieval silk knit garments and ancient Spanish graves, to eventually make its way into Scandinavian tapestries and beading. Yet Marit's decision to start knitting her mittens turned out to be a particularly magical moment in time.

Norway wasn't always an independent nation. After the Black Plague had halved its population, Norway became part of Denmark for four centuries, losing much of its national identity. By the time this '400-year night' slowly came to an end in the 19th century, Norwegians were hungry to rediscover their unique culture. What was typically 'Norsk'? Marit's mittens provided the answer. The perfect combination of folklore and fashion, made by a Norwegian girl in a small Norwegian town, her 'selbuvotter' were primed to become a big hit. As their popularity exploded, a local cottage industry was born: women were taught the pattern from girlhood (a pair of the mittens became the customary gift from a girl to her fiancé) so they could knit and sell their own. By the 1930s, women in Selbu were knitting 100.000 pairs annually, allowing them unprecedented independence.

Today, knitting machines and mass production are responsible for the lion's share of products featuring Marit's 'selburose', which has become the emblem of Christmas, winter and 'hygge', that other Scandinavian export. Still, in 2019 Norway was ranked as the world's best country for women*, with a perfect score in women's financial inclusion. (As a comparison, Sweden and Netherlands shared a 9th place on the list). Yes, we still have a long way to go when it comes to women's rights, but for now, I gladly give Marit's hand- and heartwarming fairytale the happy ending it deserves.

* According to the Women Peace and Security Index

slip it to me

mini vibrator