Art after #METOO

When Wim Pijbes became the Rijksmuseum’s director in 2008 (the most prestigious museum of The Netherlands), the first acquisition he made was my feminine feminist ‘Bare Bottom Dress’, comparing it with Mondriaan’s paintings and Rietveld’s iconic chair. A bold move, and typical for the dapper art historian with the rebellious streak who made the world news by breaking protocol and shaking hands with Barack Obama in front of Rembrandt’s Night Watch. As soon as the #MeToo movement hit the art world, I couldn’t wait to sit down with Wim and talk about the consequences of this historical event. “It all goes back to Eve picking the apple.”

Marlies: Wim, how do you see #MeToo’s effect on the art world?

Wim: There are many different sides to it. The #MeToo discussion itself seems to center around events that have come to light during the past year and a half. I think we can all agree: many unacceptable things have happened, also in the art world. At the same time, as an art historian, I observe that from the beginning of our visual language there has been a power dynamic between the artist and his subject, most often a woman. The #MeToo discussion has greatly influenced the way we assess this dynamic, and the question is: does that change the way we see famous works of art like the Venus de Milo or Manet’s ‘The Luncheon on the Grass’? I think the recent controversy around Balthus’ painting from 1938 called ‘Thérèse Dreaming’ really shows that shift of awareness.

Marlies: Yes, Balthus portrayed a pubescent girl – leaning back on a chair with her underwear visible – with a sensuality that is now considered very inappropriate. There was even a petition for removal from the Met!

Wim: It’s a perfect example of a redefinition of boundaries. What is socially and culturally acceptable? Well, that is constantly changing. And even though the Met decided to keep the painting on display, the outrage surrounding the incident really shows the power of the image: it’s a universal language with a direct impact, loaded with content and meaning. It’s why the image has been feared by political leaders throughout the ages.

Marlies: And throughout the ages, through images, women have been objectified. It seems that the image of the woman as an object of desire became so engrained in our society, that we started behaving that way. If a woman is an object, surely a man can touch her ass whenever he likes? The #MeToo movement is definitely challenging that.

Wim: Luckily, yes! In his book ‘Ways of Seeing’, John Berger wrote that a woman is almost continually accompanied by the image someone else may have of her. She is conditioned to see herself that way. Men look at women; women watch themselves being looked at. That is because we have a visual tradition, in our Western culture at least, that goes all the way back to the moment Eve picked that forbidden apple.

Marlies: One of the greatest acts of heroism!

Wim: Eve convinces Adam to take a bite, God punishes them by making them feel shameful, and from then on, Eve is Adam’s subordinate. And that is how women became depicted in our art: as always being aware of their guilt, as always being aware of being observed. And Adam? Adam merely looks perplexed at having been thrown out of Paradise. Try this little experiment for yourself: think of any famous female nude painting, Titian’s Venus of Urbino for example, and replace the woman with a man. The challenge is to imagine the man with exactly the same expression. And you know what? You can’t! In other words, a female nude has a different meaning, a priori, from a male nude. And it is so hard for women to free themselves from that objectification that we needed a disruptive event such as #MeToo to shake things up.

Marlies: We are basically addressing 3 different types of issues within art: the objectification of women in images, the violation of women during the process of making these images, and the artist who has shown transgressive behavior in his private life (but who might not have expressed that in his art, because he paints only landscapes, for example). How far do you go, as a museum, in showing your disapproval? Would you destroy art?

Wim: Destroy, no. Banning a piece of art to the depot, yes, eventually. In the political domain, we have created a system of morals and values that gives everybody the freedom to have their own opinion. When we talk about art from a different era, by artists who have perhaps already passed away, who are we to impose our current morals and values on those works of art?

Marlies: We are children of our Zeitgeist.

Wim: That is exactly the reason I want to be extra careful. If I get rid of art now – burn books, destroy paintings – how will people look at that in 30 or 40 years, when there is perhaps a whole new set of morals and values? You know, Marlies, I am imagining that I’m in a museum, standing right in front of Boticelli’s Birth of Venus: a completely naked woman, depicted by Boticelli as fully aware of the fact that she is being watched by people, by men. Yes, she is a lust object. Granted. But what if there was a sign right next to the painting, explaining that this is one of the icons of Western art, signaling the birth of the Renaissance, when God was no longer central, but man, symbolized by a woman in this case? Hopefully that will be one of the achievements of the #MeToo movement in art: that a large audience will be able to have a discussion about such things, in all freedom.

Marlies: And what will you do to achieve that?

Wim: The thing is, I can’t do it alone. We will have to work on this together, men and women; it has to come from 2 sides. And we will have to be persistent, like bamboo: bending slowly, but very steadily, till we get there.

Marlies: I’m with you, Wim. Thank you very much.

MD Friends

Building bridges

From the Erasmus Bridge and the Mercedes-Benz Museum to Qatar’s metro network; Ben van Berkel’s iconic landmarks bring people together in rapturous beauty, again and again. I talked with the Dutch architect and educator about sensuality, ‘healthy’ buildings and the remarkable parallels between our designs.

MD Friends

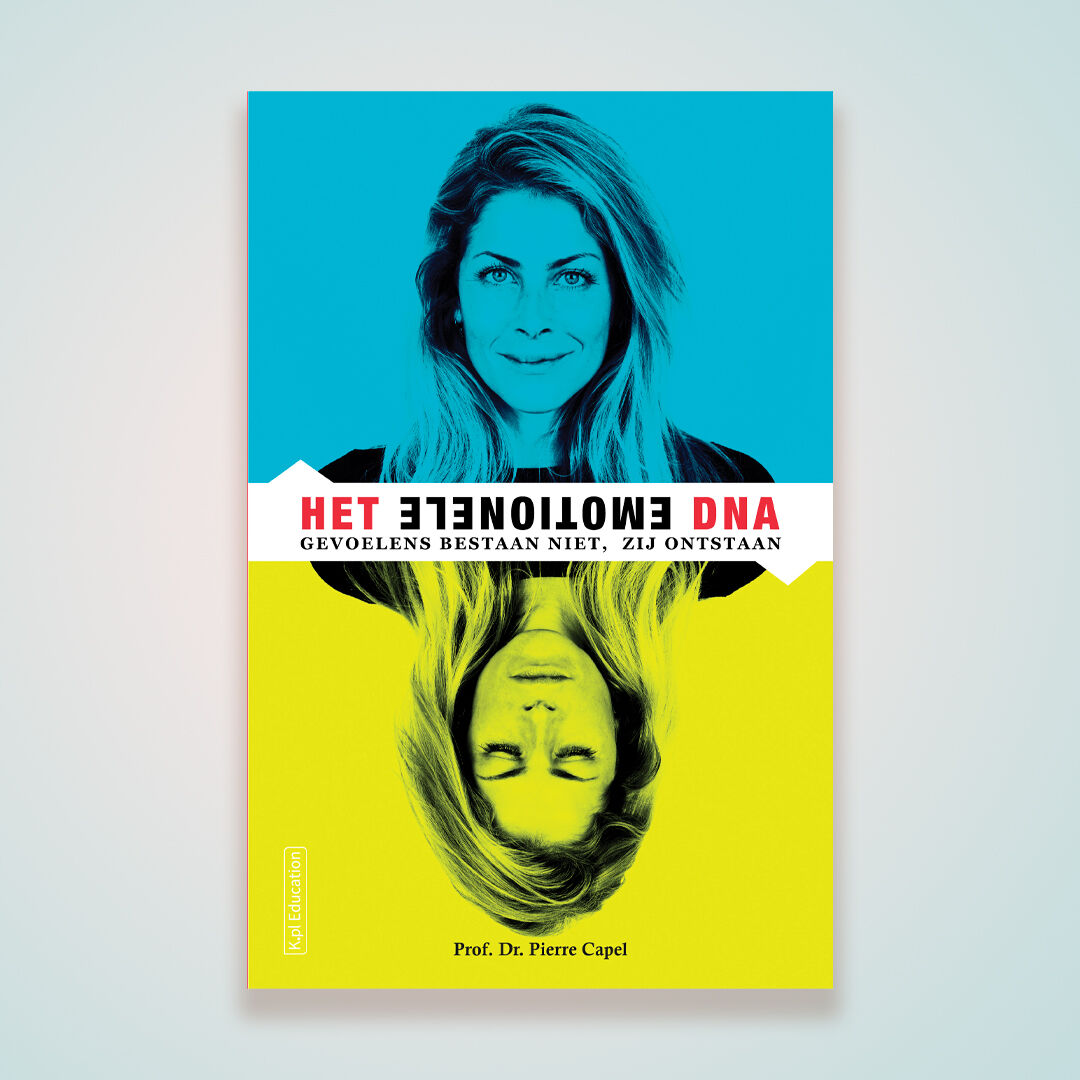

More than a feeling

Don’t ignore your emotions; they are much more powerful than you can imagine. By linking the magical world of emotions with hard science, Dutch scientist Pierre Capel, professor emeritus in experimental immunology, shows us the consequences of our feelings and the power of our minds. The message: we can do much more than we think. “Meditate. It’s the single best thing you can do for your health.”

Marlies Says

Keto curious?

The fact that I feel bikini-confident all year round is, of course, a nice bonus. But for me, the biggest payoff of following the keto diet is the way it optimizes my health and gives me tons of energy.

Marlies Says

Super (skin) food

‘If you can’t eat it, why put it on your skin?’. I pretty much live by this beauty adage. After all, with your skin being one of your body’s largest organs, anything – and I mean anything! – you put onto your skin will end up in your bloodstream.